The Tree of Eschatological Views: Revelation 1, Pt. I

Revelation is a book that has fascinated, mystified, confused, frustrated, and even been spurred by Christians through the centuries. It’s a book filled with rhythm, prophecy, and strange images that make us wonder whether the future holds hope or a bleak decline. Do we bother to open it? And, if so, do we take it at face value? Or are there hidden meanings that only the most dedicated student can decipher?

I say we bother to open it. In most cases, Revelation is either woefully neglected for fear of misinterpretation or it is myopically decoupled from the whole counsel of scripture.

And I say, no, it does not take a lifetime of decoding to understand. There is hope for all to grasp and revel in what is communicated in this book.

This isn’t going to be terribly exciting article. But I think it’s necessary to lay some groundwork.

Eschatology is the doctrine of “last things.” Colloquially, we refer to it as the study of the end times. It’s considered a niche category of theology by many, but the truth is that the eschatology you hold has great bearing on the whole of your theology. This is because, depending on when you perceive the “last things” as occurring, it will sway parts of your orthodoxy to match your perception, as well as your orthopraxy—that is the say, how you view eschatology determines what you believe about many things regarding the faith and how you practice that faith in the world.

I want to show you how I personally view eschatology. That means that none of what I’m about to extrapolate has been taken from any resource. It’s just how I organize the mass of eschatological nuances into something neat and categorical.

Two Hermeneutics

There are two main hermeneutics used to interpret the book of Revelation and other biblical prophecy, though we will see that variations of the two emerge as components of them overlap. Those two categories are: dispensationalism and covenantalism. You basically fall into one category or the other. Some refer to themselves as things like “leaky dispensationalists,” meaning they vary from standard dispensational eschatology, and some refer to themselves as things like “new covenantalists,” meaning the same on the covenantalism side.

Dispensationalism

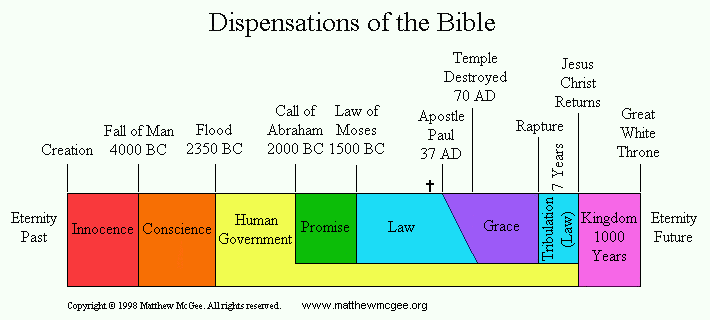

However, the fundamental doctrine of dispensationalism states that scripture is read very literally and is divided into 7 dispensations (innocence, conscience, human government, promise, law, grace, and kingdom); Israel and the church (the Jews and Gentiles) are separate peoples of God and are dealt with differently. Different dispensations are meant for either Israel or the church, or different parts of the dispensations apply to either Israel or to the church.

The dispensational hermeneutic would place us in the church age (the dispensation of grace) on their biblical timeline, with a resurgence of the dispensation of the law following the rapture of the church. This revisitation to the dispensation of the law is because God must finish dealing with Israel according to the dispensation they were enlightened in. This will be followed by the final dispensation of the millennial kingdom on earth.

Covenantalism

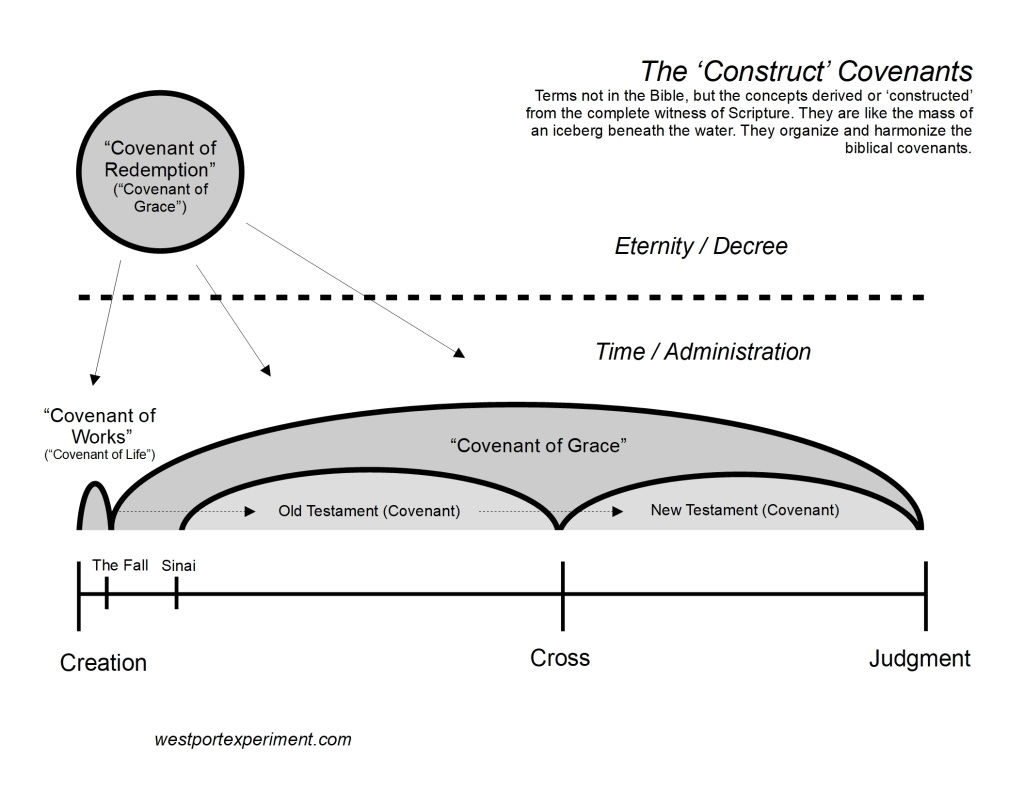

Covenantalism, on the other hand, divides scripture into a series of covenants—the covenant of redemption (made within the trinity), the covenant of works (made with Adam), and the covenant of grace (made with everyone after Adam who is in Christ, including Old Testament followers of Yahweh). Israel and the church are one people and are dealt with in the same manner regarding the law and grace.

This would place us under the new covenant under the larger covenant of grace which has been in place since the failure of Adam to fulfill the covenant of works. Anyone who does not enter the covenant of grace through Christ (who fulfilled the covenant of works on our behalf) is still under the original covenant of works. That means that a person who does not escape judgment by being hidden in Christ will be judged according to whether he himself has kept the covenant of works.

So, these are the two basic hermeneutics under which a person’s eschatology must be filed: dispensationalism or covenantalism.

The Timing of the Fulfillment of Revelation

There are also two subcategories that further delineate eschatological beliefs. The first subcategory has to do with the timing of the fulfillment of prophecy in Revelation and how much of it has been fulfilled:

Preterism: all prophecy in Revelation has been fulfilled

Partial preterism: the prophecy of Revelation is being fulfilled; some is in the past, but part is yet to be fulfilled

Historicism: related to partial preterism but slightly different; the fulfillment of Revelation is ongoing and particular historical events in relation to the church are symbolized; (this has become pretty unpopular the longer history has unfolded)

Futurism: most of Revelation (particularly ch. 4-21) is yet to be fulfilled in the future, particularly after the rapture of the church, which is said not to be found after chapter 4

The Nature & Timing of the “Millennium”

The second subcategory has to do with the interpretation of the “1,000 year reign” or millennium mentioned in Revelation 20:1-6. Whether it is interpreted figuratively or literally, and whether Christ returns before or after either a literal or symbolic 1,000 years. There are three views:

Premillennialism: Christ returns pre (before) a literal 1,000 years

Postmillennialism: Christ returns post (after) a literal 1,000 years (or a long period of time) (this is the more literal version of postmillennialism)

Amillennialism: The symbolic variant of postmillennialism; the 1,000 years is symbolic and Christ returns after a (which means “no”) 1,000 years

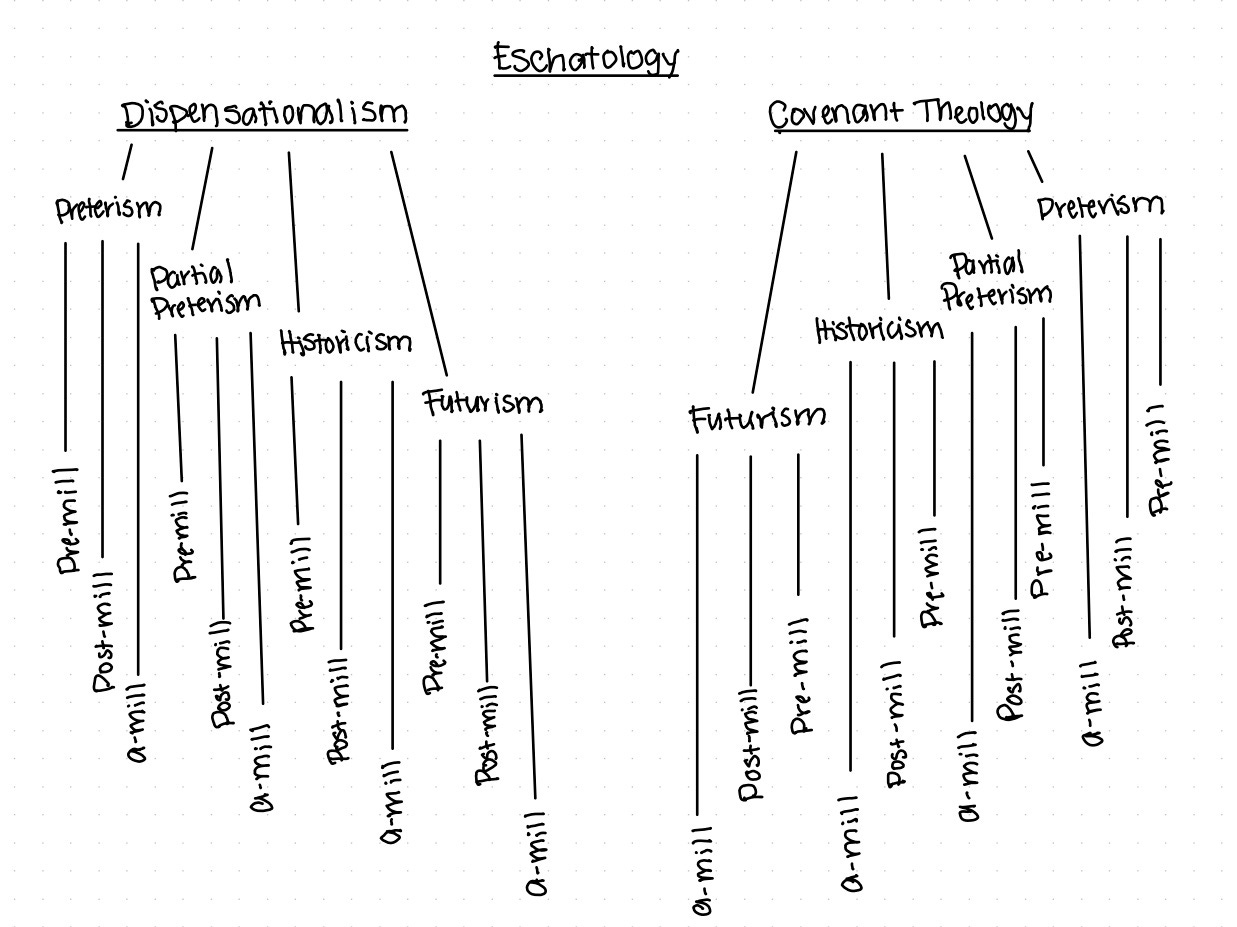

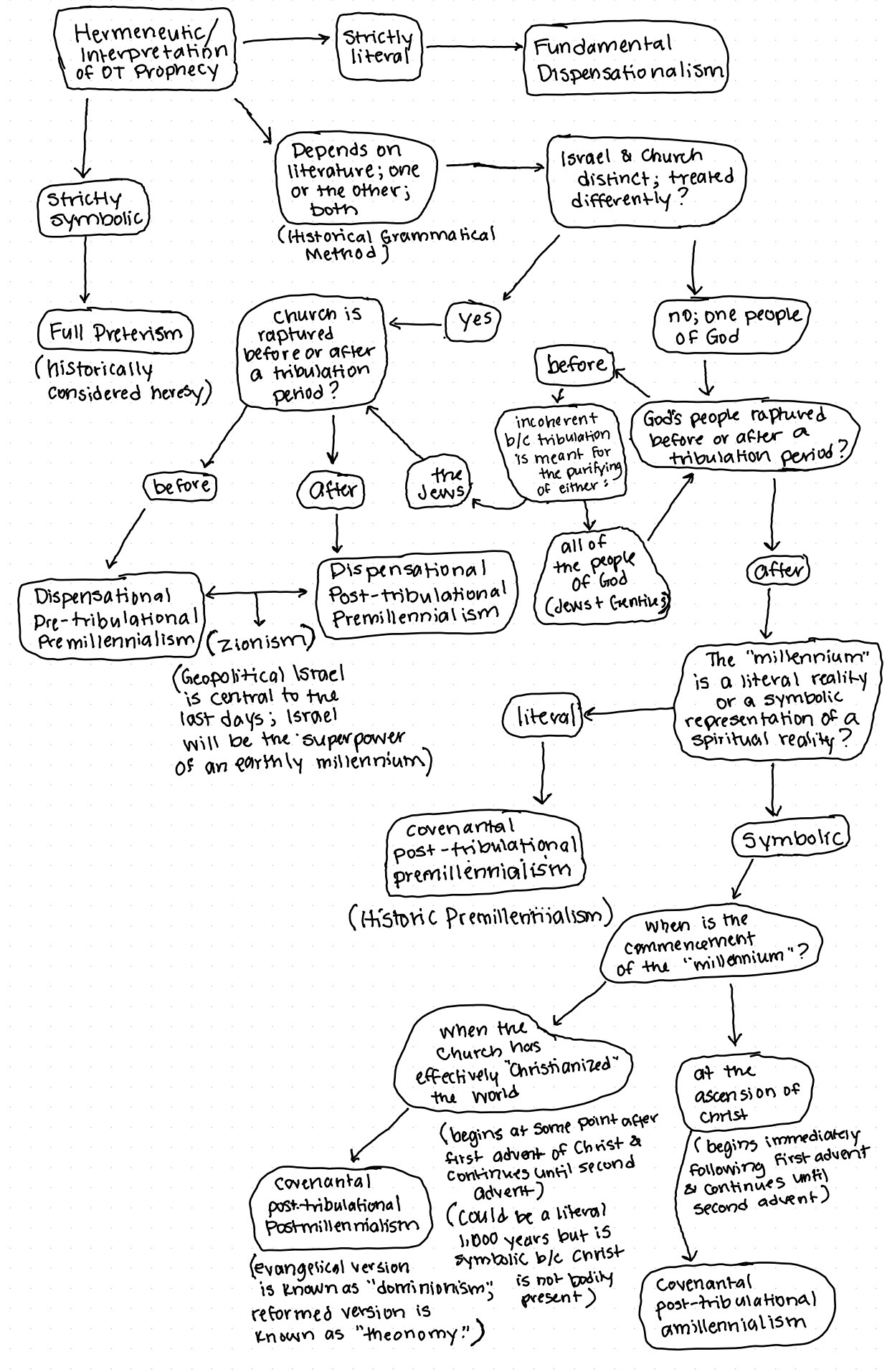

So, we end up with a tree that would look something like this to map out our options when defining our eschatology:

However, there’s a problem.

The Handful of Coherent Options

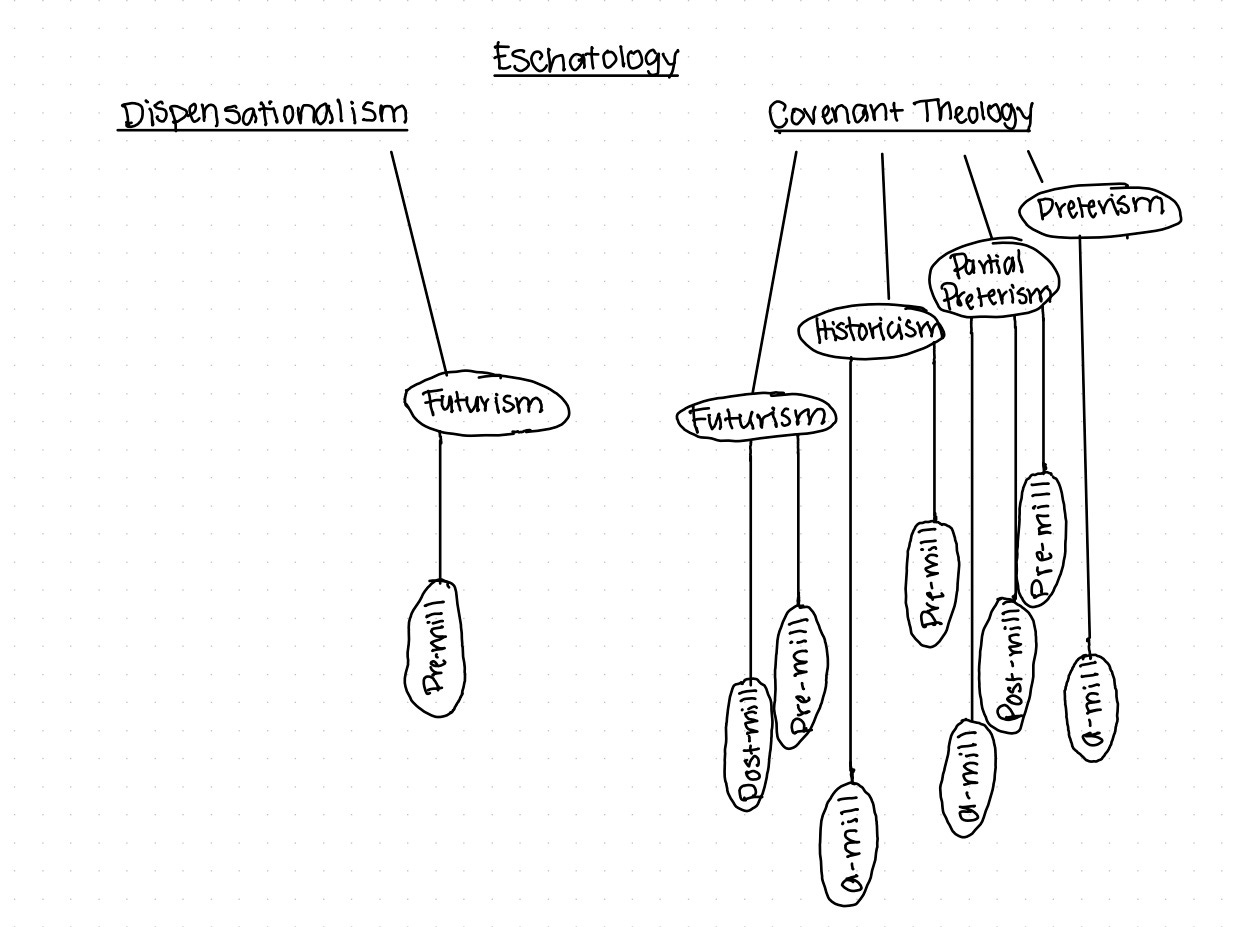

Even though this tree comprises all the different possible combinations of these categories and subcategories, not all the combinations are actually possible, because they are not all coherent. A coherent tree of eschatology options looks like this:

1(See footnote on why particular views are compatible and why others were eliminated)

(If you want more explanation regarding why particular options were not viable, feel free to comment.)

Two Stand-Alones

Looking at this new tree, it behooves me to tell you that if you are a dispensationalist, you can see this illustration that you stand alone on the eschatological landscape. The rest of church history does not really agree with you. Dispensationalism did not arise until roughly 200 years ago. Either you are right, against ~1,800 years of church history (including the early church fathers, the reformers, and the puritans), or you are very mistaken about the nature of eschatology.

Preterism also stands alone against the backdrop of church history. Preterism is historically considered heresy by the universal church. The reasons for this are multi-faceted. Every error, from a disavowing of literal bodily resurrection of the Christian (and by extension, a disavowing of the bodily resurrection of Christ) to the second coming and final judgment having already occurred in finality in the first century, lends the full preterist view to being outside of the orthodox Christian faith. So, really, the tree should not include this option. The preterist is at odds with the historic universal church as much as the dispensationalist is on the opposite end of the spectrum (though dispensationalism does not quite step out of the realm of what is considered orthodox; we do heartily consider dispensationalists our brothers in Christ while a preterist warrants further investigation).

The remaining options all have what we would call the “already/not yet” dynamic that the church has been familiar with for centuries. This means that we have already experienced the fulfillment prophecy… but also not yet in its fullness.

Still confused about what exactly your own view of eschatology is? Use the flow chart I created below to help!

What’s Your Eschatological View?

Start here:

A succinct introduction to a bold and expansive topic, but I think it is necessary to map out visually what can quickly become a confusing tangle of labels and -isms. I hope it’s been useful for you and that you have been able to identify where you are on the eschatological tree. Now that you have your label, we will move forward and test it.

Dispensationalism is fundamentally opposed to any sort of preterism because preterism purports all of Revelation being fulfilled in the first century church, so all possible combinations are eliminated.

Dispensationalism is also generally opposed to historicism, since dispensationalism places most of Revelation in the future after the rapture of the church and historicism maintains that most of it has been fulfilled in the church through the course of history.

Dispensationalism can practically only be premillennial because of its literal hermeneutic.

Covenantalism is only compatible with preterism if the millennium is either taken figuratively, so even though it technically differs from amillennialism, amillennialism is the only somewhat coherent choice.

Partial preterism (and to some extent, historicism) classically goes hand-in-hand with covenant theology. Because there is only one people of God, all millennial positions are compatible covenant theology.

Covenant theology can be taken a futurist direction, but since there is only one people of God, future amillennialism is not an option.